That said, I was thrilled when I learned SPJ- Keystone Pro Chapter awarded me first place in the “Feature Story – Non Daily” category for my Super Lawyers NY profile of former Homeland Security Director Jeh Johnson. Thanks, SPJ!

This article was also named best in show by the local and national chapters of the National Federation of Press Women.

I pasted the article below. You’ll also find it at: https://www.superlawyers.com/articles/new-york/the-public-service-call/

You can read the list of SPJ Keystone winners here: https://keystonespj.wordpress.com/

You’ll find the winners of the NFPW awards here: https://www.nfpw.org/2023-sweepstakes—contest-winners Yes, it says I’m from Minnesota, but as the old saying goes, “You can call me anything, just don’t call me late for dinner.” Or an award of any kind.

THE PUBLIC SERVICE CALL

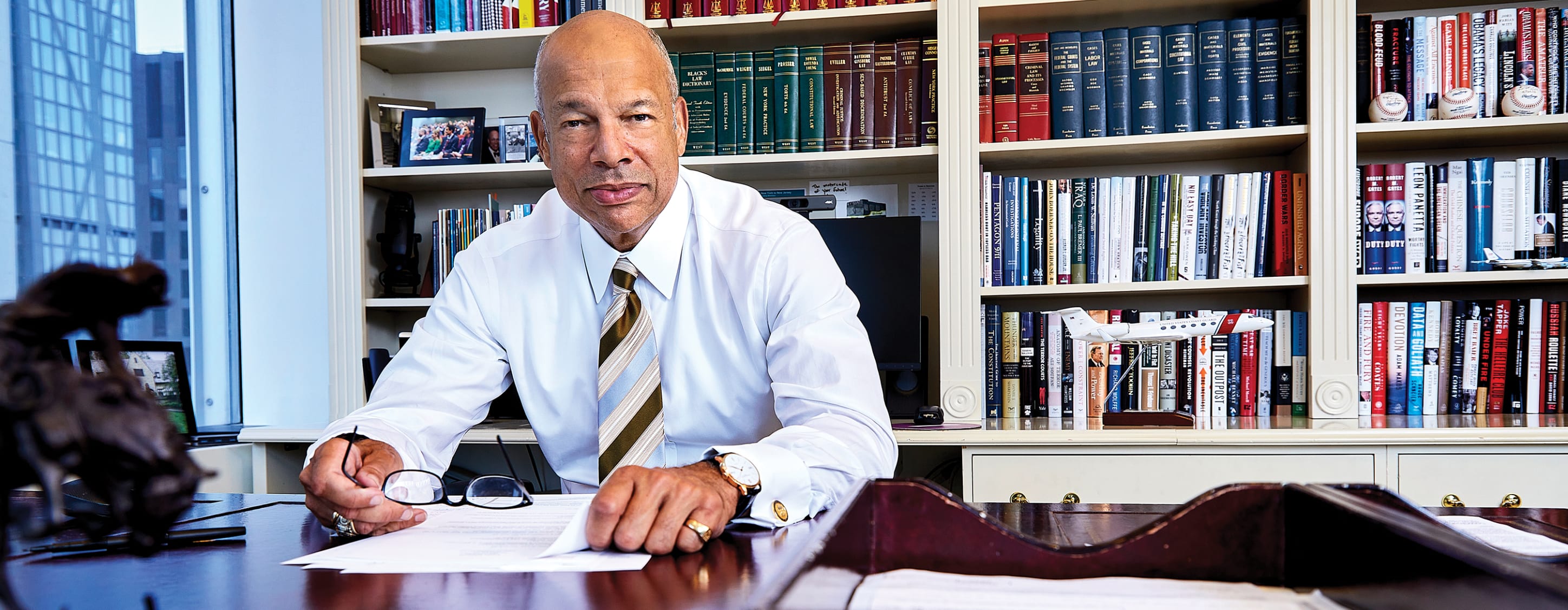

Jeh Johnson keeps giving back to his country

Published in 2022 New York Metro Super Lawyers magazine

By Natalie Pompilio on September 27, 2022Share:

When Jeh Johnson discusses his role in making the legal case for killing Osama bin Laden, or ending the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, his voice is measured and thoughtful, its depth adding gravitas.

When the conversation turns to his newest gig, hosting a R&B-focused public radio show, WBGO’s All Things Soul with Jeh Johnson, some of that gravitas goes by the wayside.

“I’ll be back on the air tomorrow, 10 to 4, begging for money,” he says of a co-hosting fundraising appearance, then raises his voice like a carnival barker: “Call 1-800-499-9246 right now!”

Private life is working out well, Johnson says. A partner at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, where he advises on matters and issues “mostly in the high-tech space,” Johnson serves on multiple boards, including those of Lockheed Martin and U.S. Steel, and acts as a trustee for organizations such as Columbia University, the Council on Foreign Relations, the 9/11 Memorial and Museum, and the Center for New American Security, a think tank. He frequently shares his insights on TV and in print, one month talking immigration on CBS, the next penning a post-Uvalde Washington Post op-ed proposing the release of graphic photos of mass shootings to awaken the public. “We need an Emmett Till moment,” he wrote.

And he has more time for his family—wife Susan, daughter Natalie and son Jeh Charles Jr.—and his hobbies, like his model trains. (He once said that in a second life he’d like to work as a NYC subway motorman, preferably on the #7 Flushing line.) Then there’s his radio show, Saturday mornings on 88.3 FM, “about as far left on the dial as you can go,” he says.

But would he give it all up again and return to public service as he’s done four times in the last 40 years?

“It’s not something I actively think about,” says Johnson, 64. “It would be very difficult, at this stage in my career, to unwind all that again, shed it all, and go back to public life.”

Others are openly dubious of this statement.

“He’s got one more job left in him,” says Christian Marrone, a senior vice president at Lockheed Martin, who served as Johnson’s DHS chief of staff. “I don’t know where or when or for who, but his leadership is desperately needed.

“We don’t have too many leaders like him. That’s just a fact. On both sides of the aisle.”

Born in 1957, Johnson spent his earliest years in the Dorie Miller Housing Cooperative in Queens. Cannonball Adderley lived down the hall and Louis Armstrong had a home two blocks away.

His father, an architect, was also named Jeh. The name comes from grandfather Charles Johnson’s time in the Republic of Liberia as part of a League of Nations team investigating reports of slavery. It’s the name of the Liberian man who reportedly saved Johnson’s life. (Family lore says a lion may have been involved.)

Charles was also a sociologist and president of Fisk University. In 1949, he was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, where he denied being a Communist. Johnson only learned of this testimony in 2015 and marvels at it: “The grandfather of the future secretary of Homeland Security had an FBI file,” he says.

Johnson’s mother, Norma, was a Sarah Lawrence graduate who worked for Planned Parenthood. A native of Washington, D.C., Norma and her family were fiercely patriotic. “Whenever I’d go to Washington as a kid, my granduncle would insist we do a walking tour of the monuments,” Johnson says. “I’m a sure a lot of that rubbed off on me.”

The Johnson family left Queens in 1963 and eventually settled in Wappingers Falls, a blue-collar town with a large Italian-American population. “We were the first Black family in the immediate neighborhood and one of the first in the whole community,” Johnson says.

Johnson’s parents put a premium on education, but Jeh, a C and D student in high school, preferred sports and aspired to play baseball—ideally for his beloved Mets. His mother was worried about his lack of motivation but his father thought he would be fine. “He had a quiet confidence that I was going to pull it together and he was right. Sometimes it takes you years to finally hear what your parents are saying.”

Johnson was accepted to Morehouse College, but at the end of his freshman year his GPA was just 1.8.

“Then a few things happened at once,” he recalls. “I realized I wasn’t going to make the baseball team. I realized I wasn’t going to be a track star. I realized I wasn’t going to be a football player. And I thought, ‘You might want to go to law school, and if that’s true, there’s nothing else to do but study.’”

The interest in law came about, in part, because in 1975 his uncle, physician Kenneth Edelin, was convicted of manslaughter after performing a legal abortion. While the conviction was overturned and Edelin formally acquitted on appeal, the racially charged prosecution and politically influenced trial affected Johnson.

In 1976, Johnson walked into Jimmy Carter’s national campaign headquarters in Atlanta and volunteered. “I was there for the election night party and I went to the inauguration,” he recalls. That same year, his father showed him a New York Times article about the law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. Johnson still has a copy of the article in his Manhattan office and reads a paragraph aloud:

“On many levels—the celebrity of its clients, the high proportion of government officials and agencies it has represented and the frequency with which its partners move in and out of government service—Paul, Weiss is as close as any New York City law firm to the public consciousness.”

He adds: “Things were beginning to gel for me: law school, politics, public service, all of that was coming together.”

Rolando T. Acosta met Johnson at Columbia Law School. They were two of the few students of color there and became fast friends, Acosta says. “When they call on you in law school, there’s never a wrong answer or a right answer. It requires conviction about your views of the world and your feelings about the question being asked,” says Acosta, now presiding justice of the New York Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, First Judicial Department. “Jeh was totally unafraid to express his conviction, and somehow that’s carried out through the next 43 years.”

As a 3L, Johnson sought a position at multiple law firms—including Paul, Weiss. He received offers from all of them—except Paul, Weiss. “I still have the rejection letter,” he says.

But he wasn’t discouraged. He applied again a few years later and joined the firm in 1984. Four years after that, he began his forays into public service, stepping away from the partner track to work as a federal prosecutor for the Southern District of New York.

“I was on track to be the first Black partner at this law firm, but I didn’t want to just be the first Black partner at this law firm. I wanted to be an exceptionally qualified partner at this law firm,” Johnson says. As an assistant U.S. attorney, he tried 12 cases and argued 11 appeals, returning to Paul, Weiss “with more trial experience than many of the existing litigation partners.” He was elected partner in 1993.

Johnson says he always encourages young lawyers to consider a career in public service. “Avoid golden handcuffs,” he says. “You will find that even though you may make a fraction of what you could make in private practice, public service can be very gratifying and rewarding. The first few paragraphs of my obituary will be the things I did in public service.”

At Paul, Weiss, Johnson took on what he considers one of the most important cases of his private career. Roger Parrino, an NYPD lieutenant Johnson knew from his AUSA days, was accused of throwing a suspect from a building roof. Parrino wanted Johnson to represent him. “I said, ‘I don’t do homicide cases’ and it was, ‘No. I only trust you.’”

Johnson worked with police to create a reenactment of what happened to show that the fatal fall hadn’t been Parrino’s fault. Plus the only witness admitted to lying, and the grand jury declined to press charges. “Nine years later, that man was a hero at the World Trade Center,” Johnson says. “Five years after that, he was the chief homicide detective in Midtown North who reinvestigated the Central Park jogger case.”

In 1998, Bill Clinton’s administration invited Johnson to serve as general counsel of the Air Force. The fact that two of his uncles had been Tuskegee Airmen was, he says, “a happy coincidence.”

“It was very much off my beaten path, but I wanted to go to Washington to be part of a president’s administration,” he says.

Even after Johnson returned to Paul, Weiss in 2001, he stayed involved in politics. He says he was so disappointed by John Kerry’s loss in 2004, he couldn’t get out of bed for two days. But in 2006 he met one of the Democratic Party’s rising stars; later that year, he phoned for a favor. Johnson still has the original pink Post-it note: “Senator Barack Obama called.” Obama said he was considering a presidential run and could Johnson hold off on throwing his support to anyone until after he’d decided?

“You’re being asked to be on the ground floor of history,” Johnson says. “I said, ‘Barack, if you run, I am with you.’”

After Obama’s win, Johnson joined his transition team, working with Richard Verma, former U.S. ambassador to India. “Jeh and I were the two lawyers and we were given all of the legislative and legal issues that the incoming Obama defense department team would face. It was 2008 and there were super-challenging issues on Iraq, Afghanistan, Guantanamo, drones,” says Verma, now general counsel and head of global public policy at Mastercard. “We’d summarize our findings in a binder and put them on a shelf. We wondered who would get those binders.”

When Johnson was appointed GC of the Department of Defense, he got those binders.

“He doesn’t go in with preconceived notions and he’s not afraid to tell people challenging or bad news,” Verma says. “I’ve never seen him get rattled. That’s part of being a great counselor. I’ve seen him with the president, in Cabinet meetings, and the Jeh Johnson you see in his office in New York is the same one I saw then.”

Johnson was quickly tossed into the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” controversy, co-chairing the group charged with reexamining the 1994 law that said gays and lesbians could be discharged.

“The president had pledged to repeal the law. The military establishment was for the most part against it. The sentiment was, ‘We’re in the middle of two wars. Don’t rock the boat.’” Johnson says. “I was not looking to get involved in this issue, which, at the time, 2010, was really contentious, with real moral and religious objections from the other side.”

After 10 months and thousands of interviews with service members, Johnson and Gen. Carter F. Ham released their report concluding that that the law’s repeal would have little impact on military operations.

“What’s remarkable is that the arguments against repeal were identical to the arguments against racial integration of the Armed Forces. Word for word. ‘It would affect unit cohesion.’ ‘It will affect recruitment.’ Identical,” Johnson says. “Years later, I would meet active service members, at a ball game or some place, and the service member would say, ‘Thank you for what you did. This is my spouse. Five years ago, I couldn’t have introduced this person to you.’”

One of the most challenging aspects of Johnson’s work as general counsel was reviewing proposed counter-terrorism operations, particularly “targeted lethal killing off the battle space,” Johnson says, including drone strikes and the mission that killed Osama bin Laden. While the president had the final say, each operation had to move up the chain of command until it reached Johnson, who needed to sign off before it moved on to Secretary of Defense Robert Gates.

“The military quickly realized I’d be a significant stop on the train and they had to come prepared to talk to me about the intelligence in support of the operation, what we knew, what the collateral damage would be,” Johnson says. “It wasn’t simply, ‘Here’s a memo. Check yes.’”

“He’s very direct and you had to be on your toes,” says Wendy R. Anderson, who was chief of staff to Deputy Defense Secretary Ash Carter, and is now a senior vice-president at Palantir Technologies. “You never wanted to be caught not having information to give him. He was tireless in terms of the number of questions—trying to get as much clarity and as clear a site picture as possible. Never rushing.”

Johnson has described May 1, 2011 as his single best day in public service. That’s the day U.S. troops killed Osama bin Laden in Pakistan. Johnson had been in New York on 9/11, and the death of the man behind the attack provided a sense of closure, but the decisions were never easy; some caused some sleepless nights.

“He wanted to hear from all points of view, not just the ones he agreed with,” says Marrone, Johnson’s former chief of staff. “We had very hard days together, but I just loved being in the foxhole with him.”

Johnson was so hands-on that it drove his Secret Service detail to distraction, Marrone says. They’d be traveling through the capital and Johnson would have the car pull over so he could get out to talk to visiting schoolchildren. He put on a Transportation Safety Administration uniform and spent a day working the security lines at BWI Airport to improve morale. One woman, to whom he revealed his identity as head of the federal agency that managed the TSA, told him, “Congratulations on your promotion, young man!”

“That’s the kind of person he was. It was genuine,” Marrone says. “He was a Cabinet secretary, but he didn’t want to lose sight of who he was.”

Adds Anderson: “He knew everybody’s name, including the women who cleaned the building. He was part of the community in the building,” she says. “It’s doing stuff when nobody’s watching. That’s Jeh being Jeh.”

Even when Johnson returned to Paul, Weiss in 2017, he kept answering the public service call. In June 2020, NY Chief Judge Janet DiFiore asked him to undertake an in-depth review of the state courts’ policies and practices on issues on race and other biases.

Four months later, Johnson issued his report. His biggest takeaway, he says now, was not something he was asked to look into but he did it nonetheless. “It was the elephant in the room,” he says. He pulls a copy of the report from a shelf and begins to read aloud: “‘Here is the bad news … [many] complain about an under-resourced, over-burdened New York State court system, the dehumanizing effect it has on litigants, and the disparate impact of all this on people of color. … The sad picture that emerges is, in effect, a second-class system of justice for people of color in New York State.’

“I had to make that observation. This report would have lacked credibility without it,” he says. “I’m sure it was not welcomed by Judge DiFiore but I had to say it, and she, to her credit, has embraced all of this and owned all of it.”

Deputy Chief Administrative Judge Edwina G. Mendelson, who heads the New York State Unified Court System’s Office for Justice Initiatives, calls the report “100 painful-to-read—but necessary and essential-to-read—pages. It’s our most recent reckoning of racial justice in America.”

Mendelson says court systems across the country have reached out to her about the report, many seeking to learn about its equal justice suggestions. “This is legacy-making, and I don’t mind legacy-making while people are still alive and they know they are making legacy. You don’t have to wait for the funeral for the flowers,” she says. “The chief judge gave [Johnson] a job, and he chose, with great impact, to do much more.”